Supply chains agile enough to respond to ever changing client demand, yet robust enough to ensure integrity of supply must underpin the assembly services offered today by contract electronics manufacturers (CEMs). With reported incidents of counterfeit electronic components continuing to rise there is no room for complacency – from those buying contract electronics manufacturing services or those that offer them.

Supply chains agile enough to respond to ever changing client demand, yet robust enough to ensure integrity of supply must underpin the assembly services offered today by contract electronics manufacturers (CEMs). With reported incidents of counterfeit electronic components continuing to rise there is no room for complacency – from those buying contract electronics manufacturing services or those that offer them.

Whether you are already outsourcing to a CEM or currently looking for a potential provider, it’s recommended that you understand the controls they have in place to protect you. In this blog post we will look at which devices are being targeted and the more common counterfeiting techniques that are used. In addition, we will cover some of the checks your CEM provider should have in place when buying outside of the official franchise network and the levels of inspection they must carry out when the parts arrive.

Which electronic components are most at risk from counterfeiting?

Semiconductors - specifically analog integrated circuits, microprocessors, memory chips, programmable logic devices and transistors - make up the five most targeted devices.

A report carried out by IHS in 2011 suggested that these commodity groups alone accounted for just over two thirds of all reported counterfeit devices. With the sum total of application markets for these five commodity groups estimated to have a revenue of $169 billion, the profits made from these parts can be huge and will often be much higher than their passive counterparts - i.e. resistors and capacitors. They also tend to cause original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) the biggest pain when they are made obsolete or go on allocation, due to the fact they are often crucial to the functionality of the circuit.

However, that's not to say other parts are immune - there have been reported cases of tantalum capacitors remarked as low ESR devices. When you consider it’s feasible to have several hundred, or even several thousand, individual capacitors on one reel it’s easy to see how the profits stack up. And it doesn’t stop there. Incoming paperwork, bar codes, labels and outer packaging are also being targeted in an attempt to breach supply chain integrity.

What techniques are used by the counterfeiters?

The techniques used have remained fairly consistent over the years - however, the quality of the counterfeiting is on the increase.

One of the most basic techniques and, arguably, the easiest for those in that trade, is the selling of "pulls", also known as "refurbs", as new devices. Unfortunately, our insatiable appetite for low cost consumer goods continues to leave vast amounts of electronic waste piling up. Where there is waste there are opportunities and electronic components are literally "pulled" from the original circuit board, cleaned up, re-packaged and then sold on as new parts. While these parts may work, traceability is clearly lost and the buyer has no way of verifying how the parts have previously been used, stored or handled.

Then there are "blank" devices – essentially a semiconductor with a brand new outer package and leads but with no internal die - i.e. the brain. While these could pass visual goods inwards inspection checks they will fail once the printed circuit board assembly (PCBA) is tested. Over time this has forced many OEMs and CEMs to either invest in additional inspection equipment like X-Ray, or send devices out to third party test houses who have the capability to "look inside" the chip to make sure it isn’t blank.

Keen to remain one step ahead, the counterfeiters introduced a more complex technique, more commonly known as "blacktopping". This technique removes a fine layer from the top of a legitimate component, along with its part number (often through sanding) so that it can then be remarked as something else. The "base" parts counterfeiters use range from completely different manufacturers and part numbers right the way through to lower specification parts.

Clearly, if the "base" part is a different manufacturer and specification it will fail early on, but what happens if a lower spec part is used? These are by far the worst for those assembling and selling electronic products. Feasibly, they could pass initial power up tests and may even work out in the field. However, when pushed to their limits they could fail – leaving the OEM design team scratching their heads and those responsible for customer service working overtime.

If you think in vehicle terms it’s a bit like buying an original VW Golf GTI from 1975 but with a 2015 body kit and interior. It’s still a VW Golf and even has the GTI badges which people will see from the outside. It has four wheels, a steering wheel, seats and an engine. However, the top speed will be much lower, the braking system won’t be as sharp and it’s unlikely to handle the same in the corners – which could result in a serious accident.

How will a CEM validate a grey market source?

Prevention is better than cure, so to start with the CEM should have policies in place to avoid buying outside of franchised distribution unless they absolutely have to. This may seem an obvious point but with the continued pressure by OEMs to reduce cost, some CEMs may find the lure of a cheaper price from the grey market hard to resist at times.

Avoiding component obsolescence altogether is almost impossible and when devices go on allocation the CEM may have no option than to look to the grey market for product. However, before they do, reputable CEMs should inform you of the problem so you are able to explore other possibilities. For example, do you have excess stock of the device in your warehouse which the CEM provider can purchase from you? Are there any alternative devices that are approved that may not be listed on the bill of materials?

With new brokers appearing overnight when the supply/demand balance tips towards them, it is important CEMs do their research before buying from a grey market source. They should spend time finding out as much as they can about the company they are considering. How long have they been in business? Do they physically own the stock they are advertising or are they sourcing it from someone else? Tools like Google maps and street view can be useful to sanity check address details - those suppliers with only PO Box numbers should be avoided.

The CEM should also find out if the supplier is a member of ERAI and holds accreditations such as AS9120 and AS6081. The CEM will challenge the supplier on the controls they have in place to help mitigate risk and ideally seek references from others that have used them in the past. The best CEMs will have stringent supplier approval processes in place and likely to have a limited number of approved grey market sources they work with which have been fully audited.

The CEM should be clear with any grey market source on their incoming inspection requirements. The most credible grey market sources should be happy to work to these and demonstrate a level of confidence that they too take counterfeiting and supply chain integrity seriously. The best sources will reject incoming devices based on their own inspection levels before they even get to the CEM. While sometimes this can be frustrating for OEMs when up against tight schedules, this best practice approach can save huge amounts of cost and heartache further down the line.

When the parts arrive what will the CEM check for?

To begin with, the CEM will pay close attention to the incoming packaging. They will be checking the basics like spelling mistakes in the manufacturer's name or part description. Using a bar code scanner they will check the bar codes to verify they can be read and what information is contained within them. Any markings or labels that have been handwritten will cause concern.

Do the date codes listed on the outer packaging match the delivery note and those physically marked on the device? Does the date code actually make sense - i.e. is it in the future or a combination that simply can’t work, such as 0258 with the 02 representing the year and the 58 representing the week, which immediately flags a problem! The CEM will also be looking to see if the condition of the goods matches the date code information they have. For example, if a part is obsolete and over 10 years old then it is unlikely to come in brand new packaging with bright shiny leads.

For semiconductors the CEM will be checking the indent marks for consistency. They should all be the same shape, size and depth. Any differences could point towards blacktopping and remarking. The country of origin mark (often on the underside) should also be uniform and shouldn’t change across a batch.

Using a high magnification microscope and digital vernier callipers, the CEM will look at the top, bottom, sides and leads of the device. They will be looking for any signs of sanding marks and checking that the surfaces are even and the dimensions of the device match those listed on the manufacturer’s data sheet. Scratch marks on the leads could point to signs the devices have been pulled out of a circuit board.

The CEM will use a solvent solution over the top of the part to check if the part markings remain in place. If they start to smudge or come off altogether warning flags will go up. Acetone, which is slightly more aggressive, will also be used to verify if blacktopping has taken place. It is worth noting that some of the newer coatings now being applied to the tops of semiconductors, consisting of a much more convincing epoxy mix, are more resilient to this kind of test. Unfortunately, these won’t always fail the solvent and acetone tests, which is why it is important your CEM uses a range of equipment and techniques together.

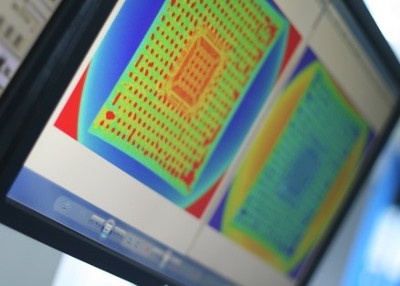

An X-Ray machine should be used to confirm if the parts received have an internal die. Counterfeit IC detectors, such as SENTRY, should be used to check the unique electrical signature against a database of known "good" parts. These specialist tools can help show which pins within an IC are active, right through to the die and lead frame consistency, which are obviously difficult to check for without.

Finally, should the CEM need additional confidence that the parts received are what they claim to be then they may arrange for decapsulation to take place, which allows access to the internal die itself. This process is, however, a "destructive" test, meaning the parts won’t function afterwards - so it is often used as a final check if the inspector is still not convinced the parts are genuine.

Hopefully this blog post has helped in understanding some of the challenges both OEMs and CEMs face with regards to electronic component counterfeiting. Having robust procedures in place at each stage of the supply chain remains critical for maintaining integrity of supply. If you are unsure of the processes and controls your CEM has in place it’s recommended you find out during your next site audit. Some will have invested heavily over the years in the necessary tools and equipment themselves. Others may be using a specialist third party test house as part of their strategy. Both of these approaches are fine – it’s the CEMs that aren’t doing either that are the ones to be wary of.